Portugal on the edge of Europe? The seafaring of Portugal changes this

The sea is no longer the end point for expansion. The seafaring of Portugal changes this. Rather, for the Portuguese, with the age of discovery, it becomes a connection to other worlds.

Portugal owned the end of the 14. Century about one million inhabitants. 40000 people lived in Lisbon. The rural population lived from agriculture, but had no own land, but worked with spiritual and secular landowners. Most of what they earned came from their landlord. The crown could recall them at any time to military and Frondiensten. Only after the peace agreement with Castile, agriculture in the north of Portugal fed the people. From the less fertile Alentejo in the south of the country people continued to migrate to the port cities. The life of a farm laborer was little worth aspiring. It would be better if one worked on the ever-advancing ships or tried to find a livelihood in the harbor.

In particular, Lisbon, Porto and Lagos, the country's three major port cities, became trade centers, connecting with other Mediterranean port cities and other newly discovered areas in the west. There met merchants, diplomats, specialists in navigation, cartography and shipbuilding with members of bourgeois families who wanted to engage in profitable overseas trade, and representatives of the royal family, who watched the new developments.

Although Portugal had already expelled the Moors from 1249, there were still Jews and Moriscos, Christians mingled with the Moors, living in the land, who could pass on their knowledge. Occasionally Black Africans could be seen coming here via Moorish trade routes long before the Portuguese thought of discovering new areas.

Knowledge is power

Heinrich, the navigator, is often portrayed as the coordinator of the Portuguese Exploration Triangle. Whether he actually did so can no longer be clearly demonstrated from the sources of the time. He was certainly very much interested and was undoubtedly someone who wanted to recognize and implement the possibilities of the times.

But he wasn't the only one confronted with the changes that were in the air. It is difficult to say what the Portuguese of the time knew and what they did not. This certainly depended on what social class he belonged to, whether he lived in the hinterland or on the coast and how high his level of education was. Marco Polo's report, which described his experiences in China at the end of the 13th century, was widespread. John Mandeville's writings told of the riches of the Great Khan and the spices of East Asia. Rumors and news from travelers who met Portuguese on the caravan routes in Egypt and the Near East expanded knowledge. Muslim geographers explored remote areas. Ibn Battuta traveled through Africa, the Middle East and India in the mid-14th century, and his reports of fine silks, gold and ivory also reached Portugal. Iberian cartographers processed this information and produced detailed maps.

Technical progress in the maritime sector of Portugal

The discoveries of the time were not only geographical. Without technical innovations and discoveries they would not have been possible.

shipbuilding

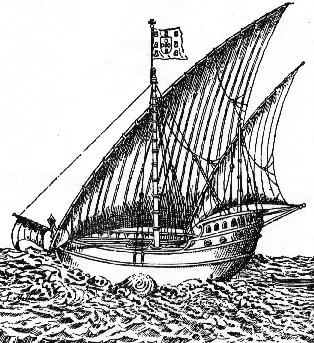

The development of caravels allowed the Portuguese to push the boundaries of European shipping. In contrast to the galleys, which were used in the Mediterranean until the 18th century, they had sails and were therefore more mobile. Their robust shape could also withstand the swells of the Atlantic. Caravels were not a uniform type of ship, but they had certain characteristics in common. The ships varied in size depending on the purpose and length of the voyage. They usually had three to four masts, three of which had large square sails and one had a triangular lateen sail.

It is no longer possible to determine where the lateen sails came from. When the Roman Empire collapsed in the 5th century AD, all ships had square sails. After that, there are no records of seafaring in the Mediterranean until the end of the 9th century, when ships are mentioned using triangular sails under a sloping yard, a square sail. Why these are called “Latins” is not known. It was probably the Arabs who introduced them to the Mediterranean. However, whether they are Arab or Phoenician discoveries is not clear. By the 13th century they were known throughout the Mediterranean and began to spread around the coasts of Europe. The first ship types to use lateen sails were the Hanseatic Holk (around 1470), the Spanish caravel (around 1490) and the Spanish Nao (around 1490). Lateen sails made it possible to sail with the wind. Ships no longer had to tack before the wind to make progress.

ship forms

In the 15. Century, the seagoing ships were getting bigger. Gradually the ship types of Northern and Southern Europe converged. In the course of the 15. and 16. Century changed their appearance increasingly. The castles remained large, but increasingly fused with the lines of the hull. Around 1550, the large ships were receiving more and more mirrors, which gave the superstructures better hold than the round corners of the Middle Ages.

This allowed them to brave the storms of the Atlantic better, and it could be larger crews and quantities of goods housed on these ships. The new types of ships fulfilled the conditions for being used overseas.

arming

Initially, sea wars were fought with the same weapons as land wars. However, their rivals at sea also had arrows, spears, javelins, swords, lances, tanks and shields, and so it was only the use of guns that gave the new sea powers superiority on the world's oceans.

Beginning of 14. At the turn of the century, the Venetians may have used the first cannons against their competitors from Genoa. The first Africa caravels of the Portuguese had already small cast guns on the fore and aft fortress. In the 15. In the 19th century, it was decided to attach the cannons to the covers and 16. In the 19th century, special gun decks and ports were set up in the ship's hull, which could be used to fire hot broadsides at the enemy.

In the case of Southwest European ships, the superior armament imparted confidence in invading unknown waters without the crews worrying about being easily overwhelmed by the local population.

Navigational aids

Ever since man ventured out onto the open sea, he has tried to improve his means of orientation. At the time of the great discoveries, the distribution and development of new nautical charts was very important. However, it was still very difficult to navigate to the points contained therein. The fact that Gerhard Mercator divided the earth into a system of longitudes and latitudes in 1569 did not mean that one could find one's way in every direction within this grid. Determining longitude caused problems until modern times until a time measuring device was developed that was reliable enough and that could be used safely on ships.

The hand log

At that time, the latitudes could already be determined to some extent using primitive tools. The hand log was used to measure the ship's speed. A piece of wood was thrown into the water and it floated there while the ship sailed on. By unrolling a line marked in certain sections, the threads were determined, that is, the speed at which the ship moved in a set time. The only way to divide time was to use an hourglass.

The compass

The phenomenon of magnetic attraction that the compass takes advantage of was in the 12. Learned by Arabs in China in the 19th century and in the 13. Century been made known in Europe. This allowed the North Pole to be fixed and the direction in which a ship sailed to be determined.

The astrolabe

The astronomical navigation went back to the Arabs, who determined with the help of the astrolabe the direction of prayer to Mecca. On a free-hanging ring, a rotary ruler was attached, which determined the state of the sun and stars. On the ring scale then the height could be read. Portuguese and Spaniards took over this tool.

The quadrant

The measurements require knowledge of calculated values. All ships that calculate the same altitude for a given star at the same time are on the same astronomical line of reference. Over time, more and more precise tools were developed for this purpose. The quadrant was probably built around 150 BC. Invented in Greece.

The Gradstock

The Jew Levi Ben Gerson of Catalonia built the Gradstock or Jacob's staff in 1342. This consisted of a measuring ruler and three sliders of different lengths. The ruler was provided with scales, each of which belonged to a slider. The height was measured by holding the rod to the eye and moving one of the slides until its lower end aligned with the horizon and its upper end with the sun. You could then read the height on the ruler.

Cartography and the seafaring of Portugal

The usual cards of the time before the 15. Century mixed legend with reality. The knowledge of distant regions often came from fantastic sources. The Arabian middlemen in the spice trade also tried to keep their knowledge of the trade routes secret in order to eliminate annoying competition. So maps were often a representation of the European view of the world. On the Psalter card from the 13. Century, Christ is portrayed as the ruler of the world crushing dragons under his feet. Jerusalem is shown in it as the center of the world. This was only to change when the expulsion of the Moors brought the inhabitants of the Mediterranean into ever closer contact with the knowledge of Arab and Jewish scientists.

Maps of the Arabs were available to the Portuguese explorers. During their voyages of discovery, they drew their own series of maps, which, however, differed greatly from today's maps and sea maps. The portolan maps as already used by Venetians and Genoese and the Jewish cartographers Majorca were covered with wind dash lines, which should make it easier for the captain to find the way to the next port. Coastlines were shown on these charts, with favorable mooring locations marked. The strangest figures, monsters and creatures were often depicted in the countries themselves, showing how little was known about these areas and how much one was influenced by the deterrent reports of the Arabs.

So it is no wonder that legends of sea monsters, monsters and legendary figures like the priest-king Johannes, who was supposedly just waiting on the other side of the sand sea of the Sahara to cooperate with the Christian conquerors from the north in the expulsion of the Arab middlemen, persisted for centuries.

Despite the increasing knowledge, there were only a few specialists in Portugal at that time who were familiar with the nautical charts of the time and the navigation. Therefore, they often hired Arab pilots who had to bring their own nautical charts.

Life on board at the time of the Portuguese seafaring

The caravels of the early explorers set out for areas that were mostly completely new territory for everyone on board. Some of the crew had never ventured out to sea, perhaps heard of strange people who lived in regions of the world that would take them months to reach. They left their familiar surroundings behind and had to adapt to months of meager diet, hostile natives and stormy sea voyages through unknown waters. What kind of people were they who embarked on these adventures? And what was in store for them?

crews

Despite all the technical innovations, it took a strong motivation to make people embark on the venture to venture into unknown realms on the open sea. The crews of the first explorerships consisted in part of convicts who had been promised a leave of punishment if they were to survive this adventure. Bartolomeo Diaz had to turn around because of a threat of mutiny off the coast of South Africa and sail back to Portugal and was unable to fulfill his actual mission - namely to find the sea route to India. Fear, ignorance and superstition of the crew played a major role.

Nobles strove for wealth

In the centuries before the great discoveries, the Portuguese had been busy expelling the Moors from the Iberian peninsula. This gave many small noblemen the opportunity to earn their living during the wars against the Moors and to increase their social status by being awarded lands and titles for their war services. After the Moors 1492 were expelled from the Iberian Peninsula, this possibility of social advancement was eliminated. At the same time, however, there was an opportunity to gain new land, riches and fame in the new countries of Southeast Asia and on the other side of the Atlantic.

Religious orders wanted to do missionary work

Other crew members were more interested in rescuing the souls of non-Christian indigenous peoples. Various monastic orders moved their activities increasingly to the conversion of newly discovered peoples.

Over time, interest in these areas, about which one knew next to nothing, grew, and more and more curious and adventurous people embarked, who made it their business to report back home from these exotic regions of the world, be it about the unusual way of life there, the strange flora and fauna or the discovery of other new things that were not known back home.

Sailors from middle-class families, agricultural workers and farmers' families

The previously mentioned crew members were mostly members of the middle class, whose members were the lower ranks of the aristocracy and members of wealthy bourgeois families. These were well-read, possessed property, and endeavored to ascend to the higher ranks of the aristocracy. In addition, there was also the simple sailor, who did the hard work on board. This often came from the poor conditions of small farm and peasant families, who owed leases and landlords to their landlords. Frequently it was also criminals who could repay their punishment in this way faster. Mostly they could not read or write, and did not know where they were going and what dangers they would face.

Living conditions on board during the sea voyage in Portugal

Even if the new types of ships used for the voyages of discovery were larger and more manoeuvrable than all ships that the Europeans had previously used for seafaring, they were not designed for the convenience of the crew, but were supposed to make so much profit for the high investments deliver as possible. This meant that the seafarers were often crammed together for months in a confined space. In the early years of the discoveries, there were no team accommodations. Every sailor had to find his place to sleep where he found it. Only later did you take on board the hammocks that you had come to know from the Indian tribes of the Caribbean. Often the crews were housed in such a small space that you could not even turn around without entering your neighbor's bedroom. On the ships there was the command "Upturned!", In which all sleeping people had to turn to the other side at certain night hours.

Hygiene on board

Hygienic conditions on board were catastrophic. There were no latrines. Instead, it used spanned networks at the bow. Daily personal hygiene was not known on land. Often the sailors kept their clothes during the entire journey. They rarely had clothes to change. Only in the middle of the 18. Century beat the English naval doctor Dr. James Lind of the British Admiralty, the daily cleaning and washing of clothes as a means against the spread of diseases on board.

Illnesses on board

Such conditions contributed to the rapid spread of infectious diseases on these ships. For the common diseases on board, the miasm theory was developed, which said that people at sea were simply outside their usual environment. It was believed that he needed the vapors from trees, stones and earth to survive and that he could never be in his element at sea. One spoke of “Mala Aria”, the “bad air” that is responsible for the diseases. The name malaria developed from this term.

In addition to pathogens that were brought on board in these foreign countries, the germs of many diseases were also transported. The food on these ships defies description. Food preservation was hardly known. Moldy and rotten food was the order of the day. Drinking water was an equally big problem. Algae formed in the water barrels just two weeks after leaving the home port. The daily grog ration should provide at least one sip of a tolerable drink per day. Since most of the seafarers were given the task of getting to their destination as quickly as possible and bringing the goods back to Europe, they only docked on the way when it was no longer possible to avoid it. Often hostile natives also prevented the intake of fresh water or fresh food. Deficiency symptoms were the result. Scurvy was a constant companion on the ships.

These conditions meant for any seaman who ventured on such a voyage that he could no longer return alive. Everyone was aware of the real and imagined risks of such a trip. It is therefore all the more astonishing that there have been more and more sailors, merchants, missionaries and researchers who have embarked on such a risk.

The logical candidate for the first voyages of discovery - the seafaring of Portugal

It was precisely the country's location on the edge of Europe that gave it the best conditions for Portugal's seafaring and setting off into new worlds. The expulsion of the Moors had brought it into contact with new worlds of thought and knowledge. The constant armed conflicts gave rise to a society in transition that no longer wanted to forego the advantages and opportunities of social advancement. Increasing technical and scientific knowledge made technical progress possible, which made great voyages of discovery possible. And the pursuit of wealth, the desire to spread Christianity and soon the possibility of being able to bring undesirable elements to distant regions of the world where they could still serve the motherland well, quickly gave up the benefits of such a commitment recognize.

The progress of Portugal's seafaring in the Age of Discovery was a logical part of Portugal's development at the end of the 15th century. New ideas were taken up, old ones discarded, and the implementation of these was bound to result in this small country on the edge of Europe becoming the first successful exploring nation of the Old World.

Literature about Portuguese seafaring:

Urs Bitterli, Old World - New World, Deutscher Taschenbuchverlag,

Munich, 1992

Daniel J. Boorstin, Discoveries, The Adventure of Man, Himself

and recognize the world, Birkhäuser Verlag, Basel, 1985

Rainer Beck, eds., 1492, The World at the Time of Columbus, Ein

Reader, CHBeck Verlag, Munich, 1992

PM Perspective, Maritime Adventure, Munich, January 1996

Do you also know:

Text The seafaring of Portugal: © Copyright Monika Fuchs and TWO